One more element may soon be added

to the Periodic Table. On September 10, 2013, scientists reported

evidence supporting the existence of element 115.

One more element may soon be

added to the Periodic Table. On September 10, 2013, an international

team of scientists working at the GSI Helmholtz Center for Heavy Ion

Research in Darmstadt, Germany reported that they have acquired new

evidence supporting the existence of element 115. The new evidence will

be reviewed by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemists

(IUPAC), and if confirmed, element 115 will likely be given a new name

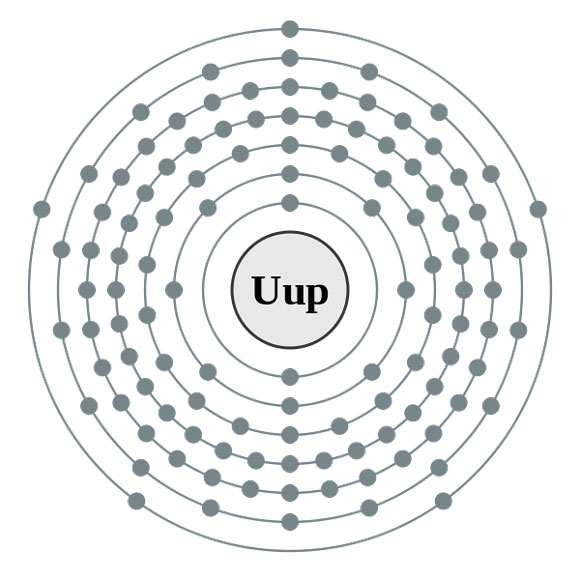

and added to the Periodic Table of Elements. Its temporary name, which

is being used as a placeholder, is ununpentium.

Element 115 is one of a number of

superheavy elements—elements with an atomic number greater than 104—that

are so short-lived, they can’t be detected in nature. Scientists can,

however, synthesize these elements in a laboratory by smashing atoms

together.

In 2004, scientists from the United States

and Russia first reported the discovery of element 115. Unfortunately,

the evidence from that research and a few more studies that followed was

not enough to confirm the existence of a new element.

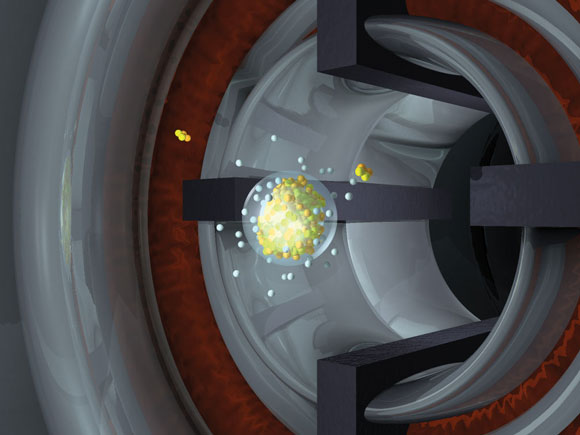

Now, scientists are developing new

techniques to detect the presence of superheavy elements. In an

experiment conducted at the GSI Helmholtz Center for Heavy Ion Research

in Darmstadt, Germany, scientists successfully bombarded a thin layer of

americium (atomic number 95) with calcium (atomic number 20) to produce

ununpentium (atomic number 115). Ununpentium was observed with a new

type of detector system that measured the photons that were released

from the reaction. The unique photon energy profile for ununpentium can

be thought of as the element’s fingerprint, the scientists say.

Creation of element 115 during a particle collision of americium and calcium atoms. Image Credit: Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Dirk Rudolph, lead author of the new study

and Professor at the Division of Nuclear Physics at Lund University in

Sweden, commented on the findings in a press release. He said:

This can be regarded as one of the most important experiments in the field in recent years, because at last it is clear that even the heaviest elements’ fingerprints can be taken. The result gives high confidence to previous reports. It also lays the basis for future measurements of this kind.

Presently, there are 114 elements in the Periodic Table of Elements. Two new elements,

flerovium (atomic number 114) and livermorium (atomic number 116), were

added to the Periodic Table in 2012. While elements 113 and 118 are

also thought to exist, their presence has not yet been confirmed.

The next step for element 115 will be for

the IUPAC to review all of the evidence to date and make a decision as

to whether more experiments are needed or if the current evidence is

sufficient to support the discovery of a new element. If the latter

occurs, the scientists who first discovered element 115 will be asked to

formally submit a new name for the element. Then, the new name will be

released for scientific review and public comment. If approved, the

element along with its new name will be added to the Periodic Table of

Elements. Element 115 is currently called ununpentium, which is just a

placeholder until its formal name is established.

The new research about element 115 was published on September 10, 2013 in the journal Physical Review Letters.

The research was supported by ENSAR

(European Nuclear Science and Applications Research), the Royal

Physiographic Society in Lund, the Swedish Research Council, the German

Federal Ministry of Education and Research, the US Department of Energy

and the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council.

Bottom line: On September 10, 2013, an

international team of scientists working at the GSI Helmholtz Center for

Heavy Ion Research in Darmstadt, Germany reported that they have

acquired new evidence that supports the existence of element 115

(ununpentium). The research was published on September 10, 2013 in the

journal Physical Review Letters. After the IUPAC reviews and confirms

the evidence, element 115 will likely be given a new name and added to

the Periodic Table of Elements.

All of this would excite only physics and chemistry geeks if not for Bob Lazar (1959- ), who introduced it to UFO lore. According to him, UFO engines use element 115 to generate anti-gravity. Various UFO nuts and wannabe scientists have taken the idea and run with it.[3] This would provide an interesting way of verifying the UFO stories told by Lazar. Should element 115 be synthesised and shown to be capable of powering anti-gravity engines, Lazar's claim would have some serious support. Obviously, given that Lazar runs a website dealing in chemicals and sales of elements, he was smart enough to pick a number higher than any element discovered at the height of his fame in order to hide it from any scrutiny; no use saying carbon or phosphorus has magical powers, as we have more than enough of that to test it.

Lazar's claims state that bismuth has "unusual gravitational properties" (this is flatly false, though it may be a misinterpretation of the relativistic effects that control the chemical properties of heavier elements) and known characteristics of Element 115 are expected to be similar (not that this matters, as the longest reported half-life of the element is 200 milliseconds). The claims further state that the element was pressed into discs, then stacked and fused into a cylinder, then milled down to form a cone, and finally sliced to form the key piece of anti-gravity fuel. Again, this is physically impossible given that the element doesn't exist in nature and has been confirmed to be as highly unstable as all the other artificially-generated elements in that region of the periodic table. A few proponents of the claim still rave that there may be a magic "island of stability" (a particular combination of protons and neutrons) that would render this element stable, but no signs of such a region of the periodic table have emerged. Some of the elements heavier than uranium possess relatively stable isotopes (on the order of thousands of years) but by the time you get to 100, fermium, even the most stable isotopes last on the order of days and it only goes rapidly down from there. Still, the island of stability is a theoretical entity that is good, real physics — but even this wouldn't help the claims made about element 115, as expected half-lives in this island are on the order of minutes and seconds, which is indeed relatively stable in a region of the periodic table where the atoms last for milliseconds or less.

If one could synthesise element 115 (specifically its predicted stable isotope) more conclusively and show it to have an incredibly short half-life and radioactive unstability (which is pretty much conclusive right now), it would show that powering any device through the use of this element would be impossible, and certainly the 500 pounds that he claimed the US government had in their possession would also be an impossible claim. Literally. As that would consist of around 4.72 × 1023 atoms, and with only 50 atoms ever made from all the collision experiments made on this subject in a decade, this would take some time for the government to procure — many times the age of the Universe, or so.

All of this would excite only physics and chemistry geeks if not for Bob Lazar (1959- ), who introduced it to UFO lore. According to him, UFO engines use element 115 to generate anti-gravity. Various UFO nuts and wannabe scientists have taken the idea and run with it.[3] This would provide an interesting way of verifying the UFO stories told by Lazar. Should element 115 be synthesised and shown to be capable of powering anti-gravity engines, Lazar's claim would have some serious support. Obviously, given that Lazar runs a website dealing in chemicals and sales of elements, he was smart enough to pick a number higher than any element discovered at the height of his fame in order to hide it from any scrutiny; no use saying carbon or phosphorus has magical powers, as we have more than enough of that to test it.

Lazar's claims state that bismuth has "unusual gravitational properties" (this is flatly false, though it may be a misinterpretation of the relativistic effects that control the chemical properties of heavier elements) and known characteristics of Element 115 are expected to be similar (not that this matters, as the longest reported half-life of the element is 200 milliseconds). The claims further state that the element was pressed into discs, then stacked and fused into a cylinder, then milled down to form a cone, and finally sliced to form the key piece of anti-gravity fuel. Again, this is physically impossible given that the element doesn't exist in nature and has been confirmed to be as highly unstable as all the other artificially-generated elements in that region of the periodic table. A few proponents of the claim still rave that there may be a magic "island of stability" (a particular combination of protons and neutrons) that would render this element stable, but no signs of such a region of the periodic table have emerged. Some of the elements heavier than uranium possess relatively stable isotopes (on the order of thousands of years) but by the time you get to 100, fermium, even the most stable isotopes last on the order of days and it only goes rapidly down from there. Still, the island of stability is a theoretical entity that is good, real physics — but even this wouldn't help the claims made about element 115, as expected half-lives in this island are on the order of minutes and seconds, which is indeed relatively stable in a region of the periodic table where the atoms last for milliseconds or less.

If one could synthesise element 115 (specifically its predicted stable isotope) more conclusively and show it to have an incredibly short half-life and radioactive unstability (which is pretty much conclusive right now), it would show that powering any device through the use of this element would be impossible, and certainly the 500 pounds that he claimed the US government had in their possession would also be an impossible claim. Literally. As that would consist of around 4.72 × 1023 atoms, and with only 50 atoms ever made from all the collision experiments made on this subject in a decade, this would take some time for the government to procure — many times the age of the Universe, or so.